Barnton

Barnton Quarry produced stone until 1914.

In 1942, during WWII, the Royal Air Force built a fighter command operations room in the quarry to operate the Turnhouse Sector (now Edinburgh Airport) of RAF Fighter Command.

In 1952, as part of Cold War precautions, the facility was expanded. A three floor R4 bunker, the highest level, was constructed and the quarry backfilled to provide a Sectors Operation Centre (SOC) for correlating information from Project ROTOR radar stations throughout Scotland. The bunker was given the code letters MHA.

In 1958 the ROTOR project was decommissioned due to the time delay involved in passing information from radar station - to SOC - to the fighter aircraft.

During the 1960s, the facilities found new use as a Regional Seat of Government and was kept ready to accommodate 400 politicians and civil servants, for up to 30 days. Although the government building was meant to remain secret, its existence was revealed to the public on Good Friday 1963 when a group known as Spies For Peace published its details. It remained operational until the early 1980s.

In 1983, ownership was transferred to Lothian Regional Council, who sold it in 1987 for £55,000 to a Glasgow developer (MacGregor Properties), but they failed to get planning permission for development. In 1991, the structure sustained fire damage. The property was put up for sale again in 1992, but before it could be sold the interior was largely destroyed by a fire in May 1993. The fire released asbestos fibres throughout the underground rooms and put them in an extreme state of dereliction. The site was then purchased by James Mitchell, Managing Director of Scotland's Secret Bunker in Fife.

Since 2011, a team of volunteers has been involved in restoration efforts to return it to its 1952 condition.

In June 2021 Historic Environment Scotland gave the site Category A listing.

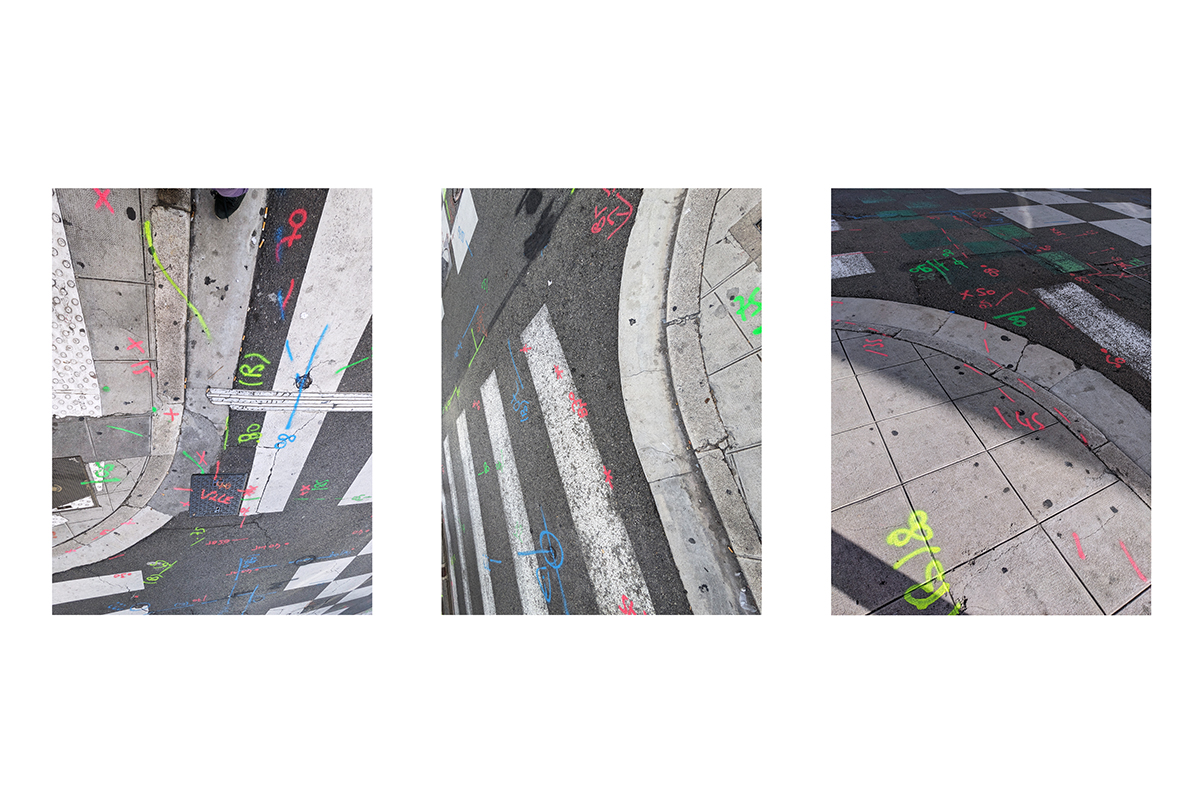

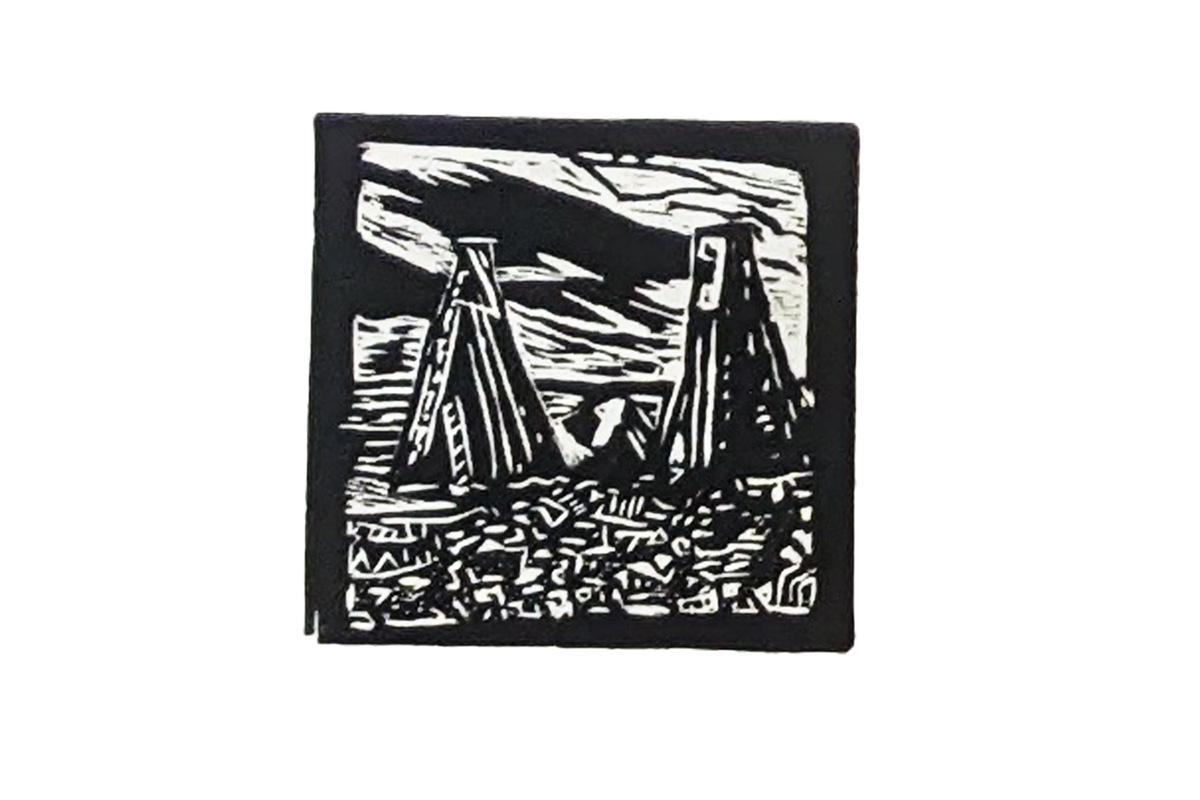

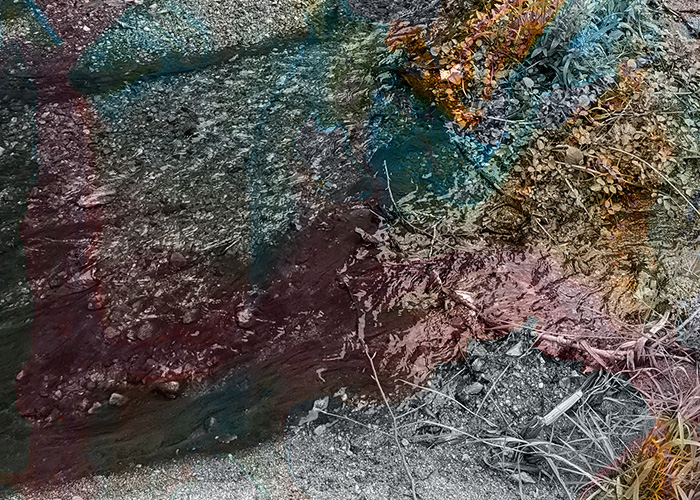

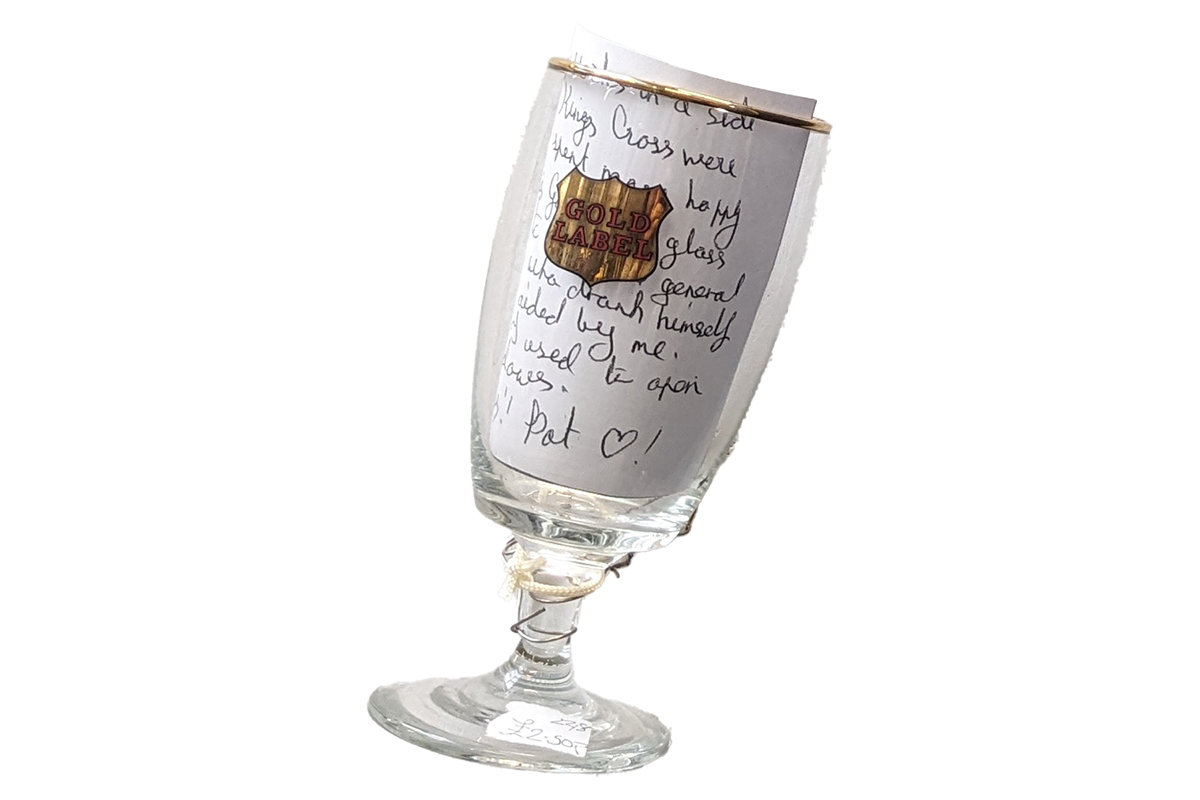

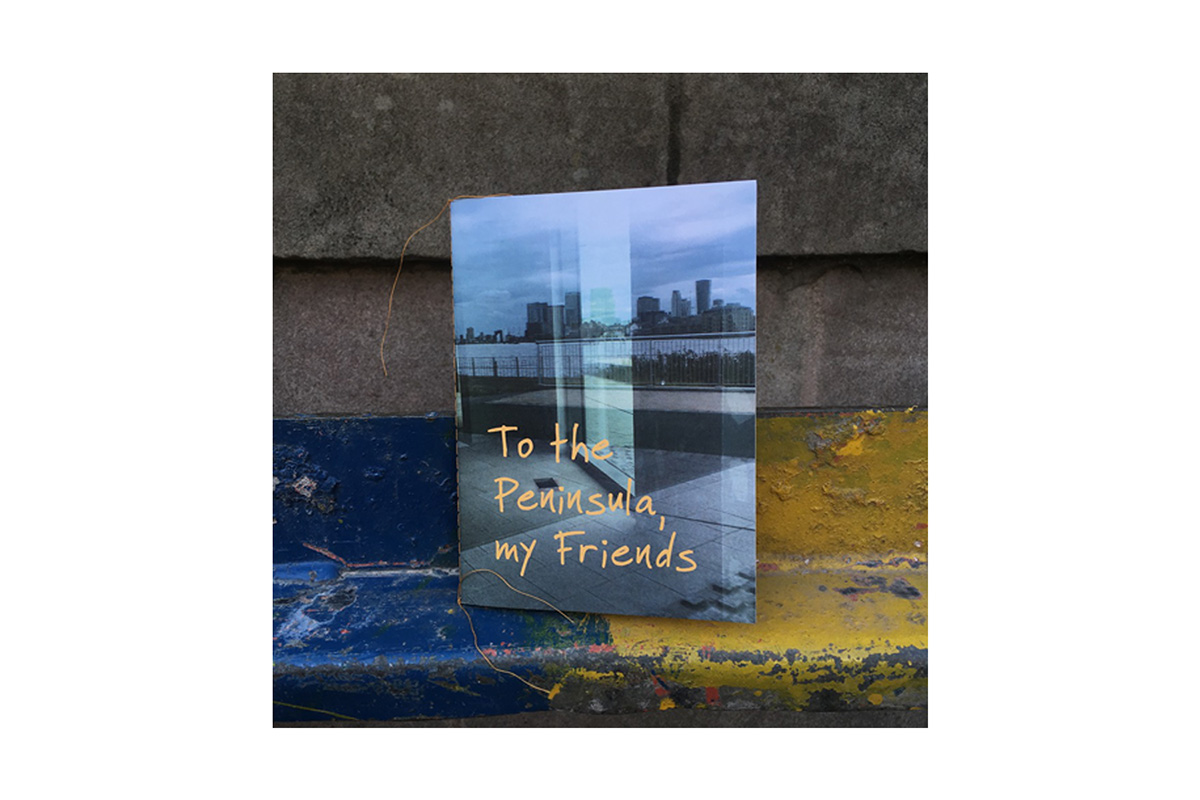

Exit is a collaborative project exploring the shapes, forms and patinas of the site.

S Borthwick, E Robson - 2024